"This semester I've actually been sitting on a revisioning Gen-ed committee, so I had some opportunities to do focus groups with my students. We talked about their experience in the classroom—not just mine but some of the other classes. We talked a lot about assignments that allow them to do hands-on learning, assignments that require some kind of multimodal composing, where there's a multimodal component to the assignment. I asked them not only about their experience but what they think they learn, and I've had a variety of answers. Some of them said that they found it easier to compose their written assignments, that they were better able to understand things like structure and the construction of an argument when they were putting it together in visual ways or working with film projects first. So I actually think that it's worked to improve the way my students compose, even the way they understand composition—that process and what that process looks like for them." Sheena Monds, UTC Senior Lecturer

As we assessed the partnership and how it affected UTC faculty and students, we reviewed how both groups felt about the scaffolding and training. We needed to know if faculty felt supported in this initiative: which methods should we continue to use, which should be modified, revised, or ended. Similarly, we needed to know if students were engaging with the projects and, if not, whether we should shift our instructional preparation to better suit students' needs.

Student Expectations and Multimodal Realities in ENG 1020

When designing the survey, because the multimodal component had been required for a few years, we wanted to know if the faculty members' opinions regarding multimodal instruction had changed at all and if so, to describe how. Responses mirrored the overwhelmingly positive feedback.

Because this partnership is committed to continually honing the support material, training, and resources for writing faculty and their students, it was important that we continue to check in with faculty about their understanding of multimodal composition and how to engage their students; some faculty indicated that they have a better understanding of multimodal composition. Others committed to continuing to revise and hone the project:

I still am trying different approaches to find that sweet spot of what challenges the students but is doable within the constraints of the semester. I still appreciate the flexibility we have with how we fulfill that requirement, but I always feel as though that assignment would benefit from more time to allow a better integration with the work we've done previously in the semester. I'd like to create an assignment that allows the student to get excited about doing it and motivated to do a really good job with it. I recognize the value of the assignment and am continuing to try to do it justice.

When we began this partnership, one issue that we knew we'd have to work to resolve was how to help the at best resistant and at worst combative faculty members who did not embrace multimodal composition. One faculty member continued to express resistance to the multimodal element:

While multimodal elements of an assignment can prove to be important creatively and rhetorically, our primary objective as English instructors is to prepare our students for academic writing at the collegiate level. Because our students need much instruction (even at the 1020 level) in constructing effective arguments with clearly written English, adding multimodal aspects as basic requirements tends to be challenging. We cannot allow another requirement to undermine our effectiveness in strengthening student writing skills.

It was in these moments that Jenn would use the authority of the WPA position to remind faculty that the multimodal element was a programmatic requirement. Then Emily could assert her position as studio librarian to soften the mandate by having a studio librarian work with individual instructors to find a reasonable compromise that met programmatic requirements while also honoring the faculty members' pedagogical perspectives.

Overall, faculty were generally supportive of incorporating multimodal instruction into their courses, but most also indicated a strong need for technical support and time and space to develop and hone effective multimodal projects.

Getting Help as a Professional

Emily's findings that a class on presentations given by someone other than the usual instructor is a positive experience for the students and results in a higher quality of presentations guided our approach to encouraging faculty to reach out to the studio librarians, rather than Jenn or their writing program colleagues (Thompson & Rhodes, 2017). Regarding their experiences working with the studio librarians, respondents presented overwhelmingly positive feedback. Over three-fourths of the faculty praised the studio librarians using a virtual thesaurus of positive terms: helpful, wonderful, invaluable, "above and beyond," fantastic, organized, thoughtful, tremendous, excellent, and outstanding.

Faculty particularly appreciated the teaching that the librarians provided at varying stages of their assignment process—from the development of the assignment: "I've had a fantastic experience working with Sarah in the Studio! She's always so helpful and organized, and I really value her input whenever I'm planning my multimodal projects"—to the introduction of the project to students: "Each time, it's been great. More often than not, I've worked with Wes for my multimodal projects. He's wonderful, helpful, and truly a teacher as well. Instead of just telling students how to do the technical stuff, he asks academic and critical thinking questions that they need to consider for their projects."

What the Professors Learned

In our initial discussions with writing faculty before the partnership began and before multimodal instruction became a required programmatic element, we found faculty to be cautious and apprehensive about teaching something that was at best unfamiliar to them, and at worst, completely unknown to them. As we assessed the partnership, we sought to check in with their comfort level, so that as we continued to program for multimodal instruction, we met our faculty's needs.

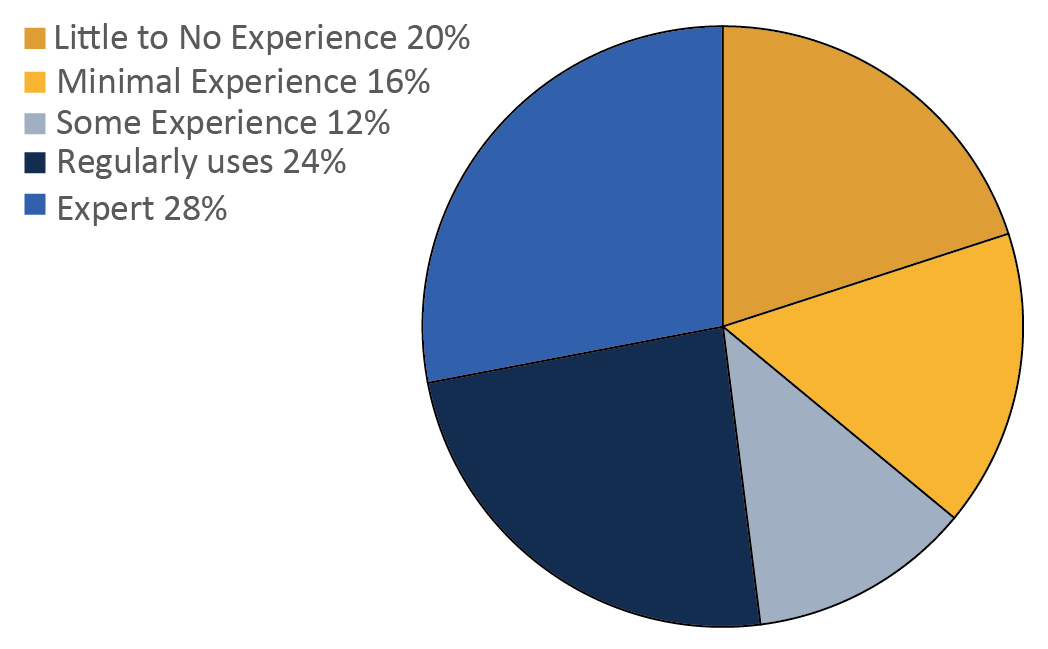

Around 35 percent of survey respondents indicated that their experience teaching multimodal composition was minimal or limited (as shown in yellow shades in Figure 4). Several respondents listed presentations or PowerPoint slides as their entrance into multimodal composition. One faculty member wrote, "[I had] very little [experience in multimodal composition instruction]. I completed some during various training programs, but I had never incorporated them into my class before the requirement."

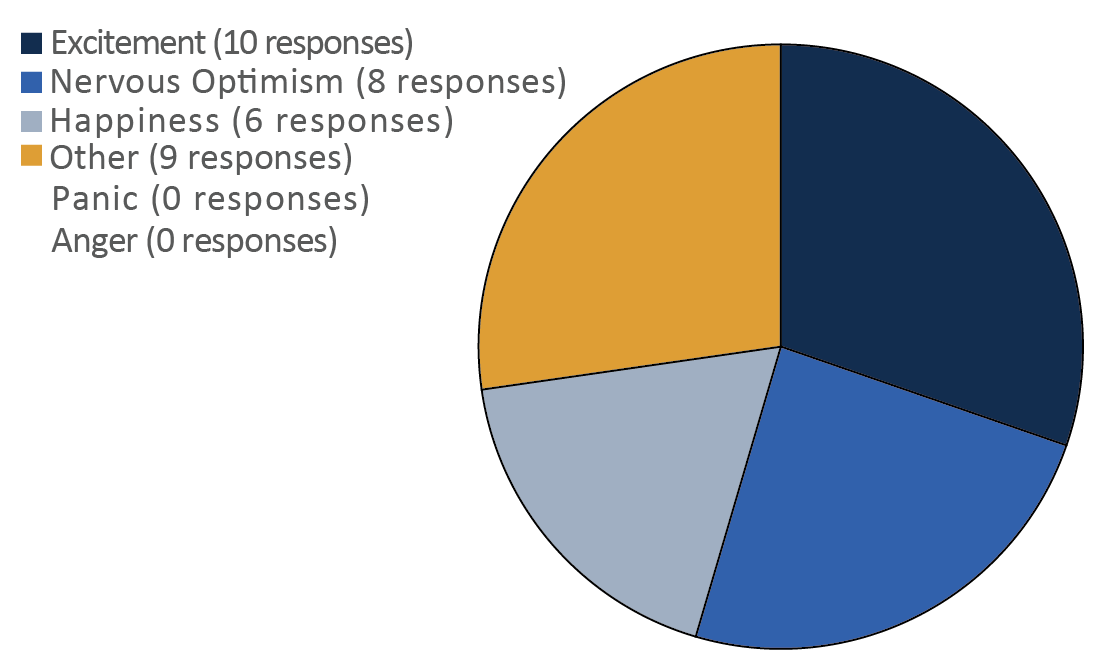

Despite the experience with multimodal instruction, faculty expressed positive feelings (happiness or excitement) about incorporating multimodal composition more than any other emotions (refer to Figure 5). We were relieved to find no respondents indicated feelings of panic or anger in response to multimodal projects. A few survey respondents indicated in their Other category comments that they felt apprehension or anxiety for themselves: "I worried about teaching something I had little experience with." Others felt anxiety their peers: "I was fine with it because I'd already been doing it, but I had nervousness for colleagues who I knew would likely panic." Some felt neutral: "Pretty neutral. I felt I had been covering that already and was glad that there was still flexibility with how we approached the requirement." And some were skeptical—"questioning the need or relevance of it"—or expressed a stoic pragmatism: "No real feelings either way. It was a new requirement, so I would learn about it and implement it."

Multimodal Project Samples

Faculty found that working with students on their multimodal projects still afforded opportunities to analyze the rhetorical elements of projects and how the students' choices affected their audiences or made their audiences do unnecessary work.

Sample assignment sheets and student work show the faculty's attention to scaffolding the project for students and connecting the work with the Studio. Student sample work, primarily presentations here, demonstrates attention to the visual and textual elements. Through the development of this partnership, faculty have engaged students in a variety of multimodal projects: brochures, presentations, infographics, Instagram campaigns, podcasts, and videos. The constraints of our IRB data collection limited our student samples to these few.

Survey Instrument

Here is the survey instrument we used to collect opinions about multimodal composition and Studio support. This survey also generated our interview participants.